Stories are the Human Operating System

I have just submitted my registration preferences for the first semester of my graduate studies at the University of Edinburgh. I start mid-September at the Futures Institute studying Narrative Futures: Art, Data, and Society. It’s an interdisciplinary MSc that excites me while mystifying most people about what the program actually covers.

My shorthand descriptor, at least until I learn otherwise, is that I am studying how stories control the world. I hope to use my storytelling prowess for the greater good. We cannot predict the future, but we can understand the possible futures ahead. Using narratives, we can strive to move society toward the most desirable futures: those that are in everyone’s best interest, rather than just those promoted by corporations or political parties.

This isn’t a new fascination for me, more an evolution. My special interest is the Discworld series by Sir Terry Pratchett. Most people would call it an obsession. I have re-read every novel in the 40-ish book series a minimum of 10 times since I started the series in the early 1990s. I re-read these books for comfort during trying times in my life, which, at this point, feels like most months since the fall of 2016. I am not sure how the past decade has flown by, but Pratchett has been there for me.

His 1991 novel, Witches Abroad, first showed me how stories function as forces that shape the world. A Russian doll of fiction, the novel follows three witches as they attempt to unravel the plot of a wicked “fairy godmother” who uses the fable of Cinderella for her own nefarious purposes. The character Granny Weatherwax sees how her nemesis and sister, Lily, is using stories to manipulate the world. As in all of Pratchett’s fiction, it is philosophy in the guise of comic fantasy.

What makes Pratchett’s understanding of stories even more prescient is that he was one of the first authors to truly grasp how technology would amplify the power of narratives. He embraced computers for writing as soon as they were available, later building a legendary screen setup to ease his writing process. When asked why he had six monitors, his cheeky response was “Because I don’t have room for eight.”

In a 1995 interview with Bill Gates for GQ magazine, Pratchett expressed concern about misinformation online, worried about the “kind of parity of esteem of information” on the Internet: how Holocaust denial could be presented on the same terms as peer-reviewed research. STP biographer Marc Burrows later called this prescient of our fake news era. Pratchett understood something crucial: when you give stories new distribution mechanisms, you don’t just change how they spread; you change their power to shape reality.

The Outline of Meaning

This insight leads us to a fundamental truth: stories are not just entertainment or cultural shorthand. Stories are the human operating system. The way your phone is built on iOS or Android, with apps designed to run on that platform, stories are the applications facilitating how we interact with the world. Our brains are the hardware and stories are foundational software.

Our minds process millions of data points per second, but stories transform that overwhelming flow into digestible chunks we can actually use. Myths and legends are plots optimised to be transferred across cultures and generations.

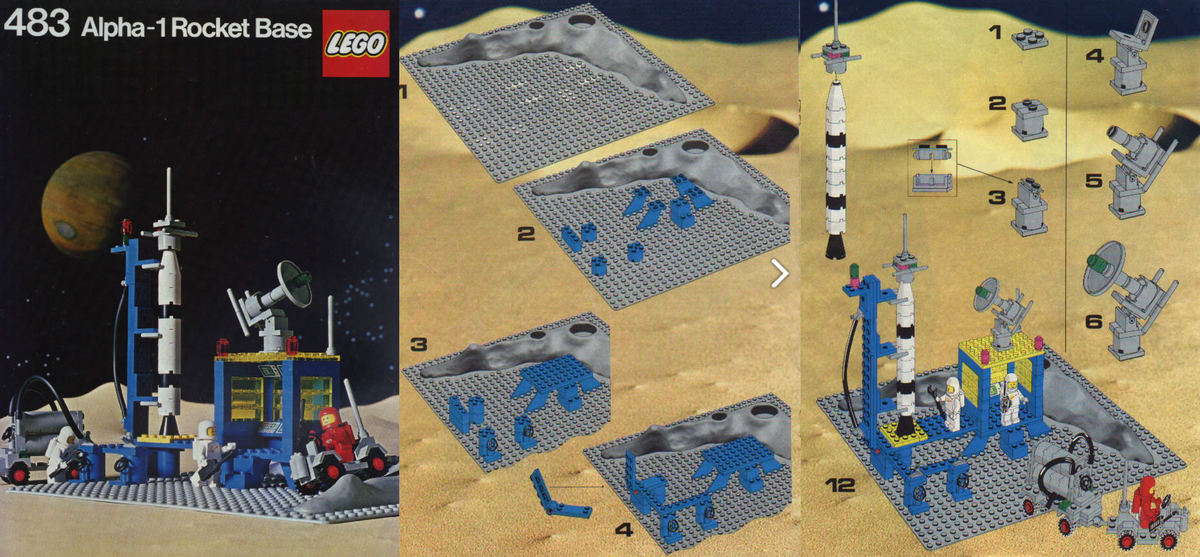

I’m about to mix my metaphors, but you are smart. For those who don’t geek out on operating systems we can also think of stories like building blocks: they must be in the shape we expect, following specific rules to fit together. A Duplo block doesn’t fit with regular LEGO pieces because they use different connection systems, but within each system, any piece with the right proportions will click into place. We love storyline archetypes because our brains are primed for those shapes. Shakespeare remains relevant because we co-evolved with those stories, which have shaped us as much as we have shaped the modern retellings.

As a child, my favourite LEGO sets were a goldenrod yellow castle, replete with a functioning drawbridge romantically named Castle Set 375, and the Alpha-1 Rocket Base Set 483 with a set of grey crater bases. The big square baseplates are the kit templates we are all born with, ready for stories to click into place like blocks on the base.

I could imagine myself as a knight jousting on horseback or as an astronaut exploring extraplanetary surfaces. Even then, I was a purist who wouldn’t mix bricks from different sets. Technically, they were interchangeable, but I instinctively understood the difference between science fiction and fantasy. The story frameworks embedded in fairytales and space operas had already taught me those boundaries.

The Pattern Recognition Engine

Going back to my operating system metaphor, books, movies, and video games are the entertainment apps which run on our narrative framework. However, there are other applications as well: the sagas we tell ourselves about our identities, our relationships, and our place in the world. Our habits function like utilities, background processes that keep our narrative self running smoothly. The personal myths we construct about our capabilities and limitations? Those are system updates we get by default, but it is our choice which ones we seek to overwrite with newer versions as we grow.

But here’s where Pratchett’s concern about information parity becomes crucial. We all consume stories, though the format may vary, ranging from books, videos, movies, episodes, articles, listicles, hymns, homilies, rants, and posts, among others. We are not even reliable narrators of our lives, quickly interpreting data into a compressed, story-like format: memories. And every time we recount those chronicles, we rewrite them over and over again until our record of a lived experience can be vastly different from that of other people who were there at the same place and time.

We are so primed for narrative formats that we even attribute plot to places where it doesn’t belong, such as in nature, onto the personalities of our pets, or by assigning intent to the actions of others. What began as an evolutionary advantage has become so powerful that it sometimes overwhelms our processing capacity.

Social media is not a problem in and of itself, the way a syringe is separate from the drug it injects. We are using these tiny screens to consume stories at an unprecedented rate. You are not addicted to screens; you are addicted to the torrent of visual anecdotes, hooked on the narrative hit of a million micro-stories every day.

We take in too much, yet so many of us feel empty and crave a comfortable yarn, like a bedtime story so we can wake up to a better world. When our pattern recognition becomes overwhelmed, we pull meaning from nothing: conspiracy theories, rumours, and mind viruses that spread because they fit our story-shaped brains better than the messy, incomplete reality.

The Mega Saga

We are so absorbed by the cavalcade of tiny tragedies and comedies streaming at us that we ignore the major narratives that control our lives. This may, in fact, be something malevolent puppet masters might want, if we frame the modern media as pulled by billionaire strings. See, there I go, seeing stories where they may or may not exist. Either way, the economic and political paradigms which we live in arc above us like the Milky Way, composed of billions of tiny stories.

When was the last time you saw the Milky Way, that dappled stripe in the sky, the profile view of our universe? Most of us can name ten streaming TV series we have watched or recent podcast episodes, but can’t say when we last really looked at the stars.

And yet, constellations reveal how deep our story processing runs. Take Orion’s Belt: three stars that have nothing to do with each other, separated by hundreds of light-years, that just happen to appear in a line from our tiny vantage point on Earth. But our story-primed brains couldn’t leave them alone. We invented a mythical hunter, complete with sword and shield, and told elaborate tales about his adventures.

We literally projected a narrative onto random points of light in space. This is our operating system at work: taking meaningless data points and automatically organising them into story format. Before screens, before streetlights, before roofs, we were already demonstrating that, given the slightest pattern, humans will construct a narrative. The same impulse that led ancient peoples to see hunters in the stars is what prompts us to see conspiracies in coincidences and meaning in algorithmic feeds.

Stories Shape Everything

This deep-seated pattern recognition explains how storytelling became my unexpected superpower in technology. Before I entered the tech industry, I studied poetry and worked in children’s publishing. Poems are tiny stories, maximum impact in the fewest words. Metaphors are a storytelling hack, taking existing components of understanding and glueing them together to form compact but powerful stories.

My ability as a storyteller has enabled me to become a more effective technical leader. At my freshman orientation for the College of Liberal Arts at Cal Poly, SLO, a father asked, “What is my daughter going to do with a degree in Communications?” And the dean shot back, “Manage engineers who cannot communicate.” This may be a faulty memory; my sister went to the same school. It may have been her orientation, but either way, my father, an engineering leader, loved to tell that anecdote as the argument for why liberal arts education matters to tech. It was a winding road to building software in my career, but that statement was downright prophetic.

I’ve learned that management is about processes and policies, but leadership is about stories and strategy. You can’t boss people into caring about something: role-based power has limits. But you can tell them a story that makes them want to be part of something larger than themselves.

Every bug report tells the story of expectations versus reality. Every user interface is a narrative about how humans and machines should interact with each other. Every product roadmap is a saga about the future we’re building toward. Stories shape software from the very beginning.

The Choice

This brings us full circle to why I’m pursuing this program at Edinburgh. People often ask me what I plan to do with my degree. I don’t know yet, but this experience will expand my ability to understand and share stories while meeting interesting people. It is an opportunity to explore innovative approaches to envisioning and building software using narrative. I can’t tell the future, but my gut tells me whatever I do next is going to be good.

This essay was written as I prepare to begin studying Narrative Futures: Art, Data, and Society at the University of Edinburgh's Futures Institute, where I hope to learn how stories control the world—and how we might use that knowledge for everyone’s benefit.